The UK government has confirmed a record-breaking £2.5 billion investment into fusion energy, aiming to push the country to the forefront of global clean power development. The money will go towards the STEP (Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production) prototype, a next-generation fusion plant planned for West Burton A, a former coal power station site in Nottinghamshire. If successful, it could represent a turning point in Britain’s energy strategy—one that could produce virtually limitless low-carbon energy without the long-lived waste associated with nuclear fission.

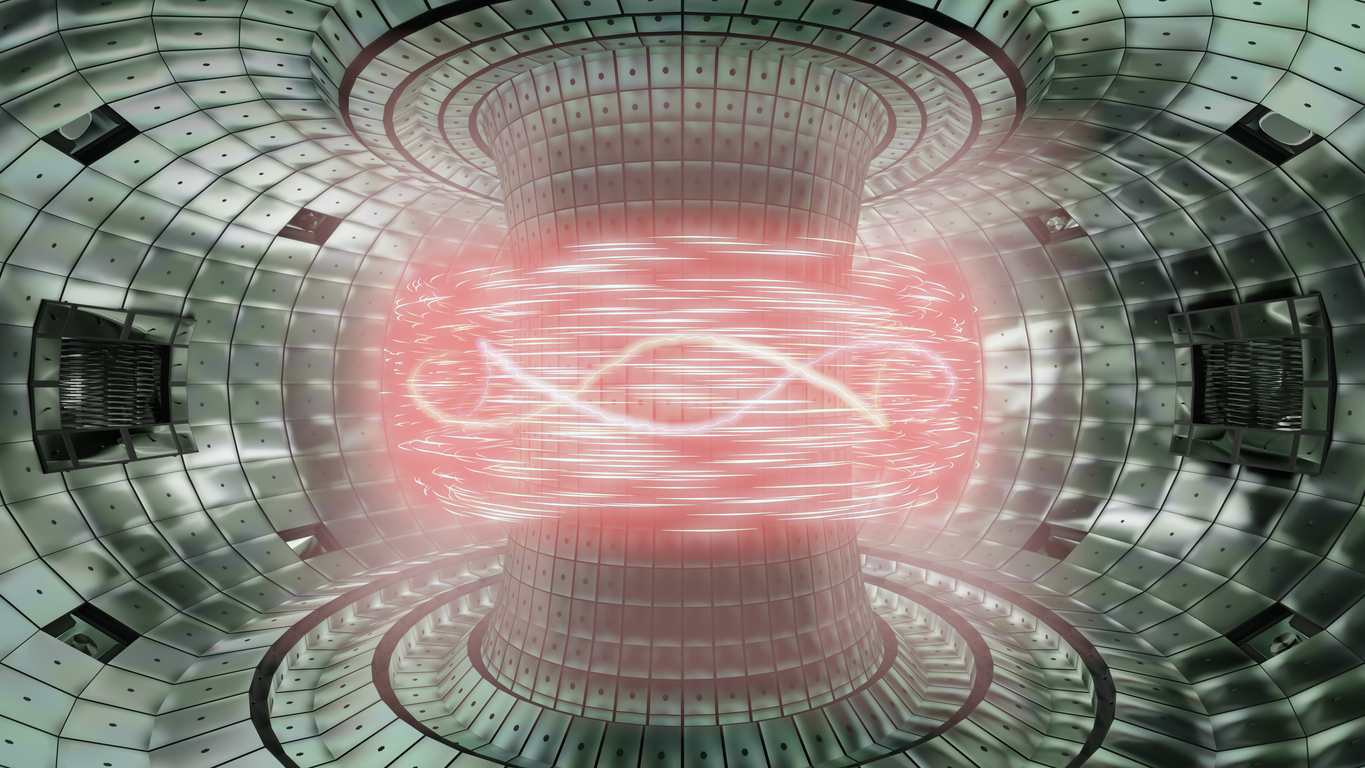

Fusion works by fusing two types of hydrogen—deuterium and tritium—at incredibly high temperatures, mimicking the process that powers the Sun. The reaction releases enormous amounts of energy with zero carbon emissions. According to The Guardian, this is one of the cleanest energy sources being pursued today, and the UK has already made notable strides through its facilities at Culham in Oxfordshire.

The STEP plant is expected to generate around 100 MW of power, which could supply electricity to roughly 60,000 homes. Though it’s still in its early design phase, the ambition is clear: get it operational by the 2040s. The idea is to take Britain’s decades of leadership in fusion research and actually build something that can plug into the grid. Culham is already home to JET (Joint European Torus) and MAST Upgrade, both key fusion machines that have shaped global understanding of the tech.

This new round of funding follows on from the £410 million already pledged earlier this year to support the UK’s fusion programme.

Ed Miliband, Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, described the move as one of the most exciting commitments in the government’s energy strategy. As reported by the BBC, Miliband framed fusion as a key part of how Britain can decarbonise while strengthening its energy independence.

STEP’s location is more than symbolic. West Burton A is part of Britain’s industrial past, a coal-fired power station that’s now closed. Transforming it into a cutting-edge clean energy site is exactly the kind of regeneration politicians have promised for years. Local leaders in the East Midlands say the project could bring around 10,000 new jobs, both directly and indirectly, boosting the regional economy and putting the area back on the energy map.

Fusion also fits neatly into the UK’s broader energy ambitions. It’s not meant to replace solar, wind, or nuclear, but rather to complement them. Renewables fluctuate with the weather, and nuclear fission brings waste and risk. Fusion, if it can be scaled reliably, offers the possibility of stable, around-the-clock energy without the same downsides. It also dovetails with Britain’s other projects, such as Sizewell C and ongoing investments in small modular reactors.

Private industry is watching closely too. Oxford-based Tokamak Energy and other fusion start-ups are racing to hit commercial milestones, and this government support helps de-risk the entire field. According to a recent piece in The Guardian, the UK’s fusion sector could bring not just clean power, but also major technological spin-offs in fields ranging from medical imaging to aerospace.

Still, challenges remain.

The STEP plant is a prototype, not a full power station, and there’s no guarantee it will hit its targets. Some campaigners have questioned whether it makes sense to build new energy infrastructure on old coal sites rather than starting afresh. Others worry that fusion is still decades away from widespread use, and shouldn’t distract from scaling up existing renewables.

That said, it’s hard to ignore the potential. Fusion doesn’t emit carbon dioxide. It doesn’t leave behind the radioactive waste that plagues traditional nuclear. And it doesn’t carry the same meltdown risks. If it works, the UK could not only meet its own net-zero targets, but also become an exporter of fusion technology—a global leader in how we tackle climate change.

The government says the investment is about creating a long-term pipeline of talent, infrastructure, and industrial capacity. And beyond just powering homes, the fusion ecosystem could support future innovation across sectors, with new materials and control systems that benefit science and engineering more broadly.

Public interest will be key. Fusion can’t just be a science project; it needs to feel like a shared national endeavour. That means transparency around timelines, budgets, and benchmarks. It also means keeping momentum—the £2.5 billion must be a beginning, not an end.

It’s easy to be sceptical about fusion. Scientists have been calling it the “energy of the future” for decades. But for once, the future feels slightly closer. And with Britain making one of the biggest commitments in its energy history, this moment might just be the start of something huge.

If we can turn an old coal site into the engine room of clean energy innovation, that’s more than good science. That’s progress.